In 2017-2018, the Cushing Memorial Library & Archives at Texas A&M University hosted an exhibit on Worlds Imagined: The Maps of Imaginary Places Collection. At the end of last year, after the exhibition had closed, a pdf of the 100 page catalog was posted online, as well as a 25-minute video view of the exhibition, hosted by the curators. Both are accessible here. They are quite fun, but one should be wary of the pronunciation of the various names and places as given by the curators. For instance, Poictesme is correctly pronounced pwa-tem (not pwa-tez-may), the setting created by James Branch Cabell (whose surname is mispronounced as ka-BELL). Cabell himself made up a rhyming couplet to correct the frequent mispronunciation of his name: "Tell the rabble: / My name is Cabell" (I've also seen this quoted as "Stop all this rabble / My name is Cabell." I'm not sure at present which is correct.). The name Dunsany is mispronounced in a way I've never heard before, as "DUNSE-nee"; whereas correctly the name is three syllables, "dun-SAY-nee"

In 2017-2018, the Cushing Memorial Library & Archives at Texas A&M University hosted an exhibit on Worlds Imagined: The Maps of Imaginary Places Collection. At the end of last year, after the exhibition had closed, a pdf of the 100 page catalog was posted online, as well as a 25-minute video view of the exhibition, hosted by the curators. Both are accessible here. They are quite fun, but one should be wary of the pronunciation of the various names and places as given by the curators. For instance, Poictesme is correctly pronounced pwa-tem (not pwa-tez-may), the setting created by James Branch Cabell (whose surname is mispronounced as ka-BELL). Cabell himself made up a rhyming couplet to correct the frequent mispronunciation of his name: "Tell the rabble: / My name is Cabell" (I've also seen this quoted as "Stop all this rabble / My name is Cabell." I'm not sure at present which is correct.). The name Dunsany is mispronounced in a way I've never heard before, as "DUNSE-nee"; whereas correctly the name is three syllables, "dun-SAY-nee""Denizens of the archives have driven themselves into sweet oblivion by pursuing false leads down cold trails to dead ends, by amassing bulging but frequently useless dossiers, and by probing dull monographs . . . yet sometimes there comes a great notion." "A Shiver in the Archives" by Gale E. Christianson

Wednesday, July 31, 2019

Worlds Imagined: An Exhibition of Maps

In 2017-2018, the Cushing Memorial Library & Archives at Texas A&M University hosted an exhibit on Worlds Imagined: The Maps of Imaginary Places Collection. At the end of last year, after the exhibition had closed, a pdf of the 100 page catalog was posted online, as well as a 25-minute video view of the exhibition, hosted by the curators. Both are accessible here. They are quite fun, but one should be wary of the pronunciation of the various names and places as given by the curators. For instance, Poictesme is correctly pronounced pwa-tem (not pwa-tez-may), the setting created by James Branch Cabell (whose surname is mispronounced as ka-BELL). Cabell himself made up a rhyming couplet to correct the frequent mispronunciation of his name: "Tell the rabble: / My name is Cabell" (I've also seen this quoted as "Stop all this rabble / My name is Cabell." I'm not sure at present which is correct.). The name Dunsany is mispronounced in a way I've never heard before, as "DUNSE-nee"; whereas correctly the name is three syllables, "dun-SAY-nee"

In 2017-2018, the Cushing Memorial Library & Archives at Texas A&M University hosted an exhibit on Worlds Imagined: The Maps of Imaginary Places Collection. At the end of last year, after the exhibition had closed, a pdf of the 100 page catalog was posted online, as well as a 25-minute video view of the exhibition, hosted by the curators. Both are accessible here. They are quite fun, but one should be wary of the pronunciation of the various names and places as given by the curators. For instance, Poictesme is correctly pronounced pwa-tem (not pwa-tez-may), the setting created by James Branch Cabell (whose surname is mispronounced as ka-BELL). Cabell himself made up a rhyming couplet to correct the frequent mispronunciation of his name: "Tell the rabble: / My name is Cabell" (I've also seen this quoted as "Stop all this rabble / My name is Cabell." I'm not sure at present which is correct.). The name Dunsany is mispronounced in a way I've never heard before, as "DUNSE-nee"; whereas correctly the name is three syllables, "dun-SAY-nee"Sunday, July 28, 2019

A Dunsany quote from James Blish?

In his Guest of Honor speech at EasterCon 21 in London in 1970 (audio, with illustrations, here), James Blish gave a supposed quote from Lord Dunsany that I have been otherwise unable to source. Here what Blish said:

I found a very similar idea in an essay "The Symbolism of Poetry" by William Butler Yeats from 1900, as follows:

Like all the arts, science fiction adds to our knowledge of reality by formally evoking what Lord Dunsany called "those ghosts whose footsteps across our minds we call emotions."Blish's talk was basically his introduction to Harry Harrison's anthology The Light Fantastic: Science Fiction Classics from the Mainstream, published in 1971. But where does the Dunsany quotation come from? Anyone? Is it even really a Dunsany quote?

I found a very similar idea in an essay "The Symbolism of Poetry" by William Butler Yeats from 1900, as follows:

"certain disembodied powers, whose footsteps over our hearts we call emotions"Apparently, either Dunsany might have slightly restated Yeats's words somewhere, or Blish might have misattributed the (slightly inaccurate) words to Dunsany rather to Yeats. I'd lean towards the latter.

Thursday, July 18, 2019

Further on the Grill/Binkin Lovecraft Collection

Back in March, I wrote on the Lovecraft Collection of Jack Grill and (later) of Irving Binkin. It's posted here.

This is a follow-up, bringing the story to the present as far as I am able.

The

proprietor of the Book Sail must also be described as eccentric. John

Kevin McLaughlin (1942-2005) was the only child of an IBM executive

and his wife. He grew up in Endicott, New York, and graduated from

high school there, after which he attended college at World Campus,

which was a float that went around the world. He married (and

divorced) twice, and was survived by two sons from his first

marriage. He founded the Book Sail in Anaheim in 1968, and moved it

to a larger location in Orange in 1975. Meanwhile he amassed a

legendary collection of antiquarian books, vintage comics, pulp

magazine, and movie scripts and memorabilia. He must have purchased

the Grill/Binkin collection of Lovecraft manuscripts in the late

1970s or early 1980s.

The

proprietor of the Book Sail must also be described as eccentric. John

Kevin McLaughlin (1942-2005) was the only child of an IBM executive

and his wife. He grew up in Endicott, New York, and graduated from

high school there, after which he attended college at World Campus,

which was a float that went around the world. He married (and

divorced) twice, and was survived by two sons from his first

marriage. He founded the Book Sail in Anaheim in 1968, and moved it

to a larger location in Orange in 1975. Meanwhile he amassed a

legendary collection of antiquarian books, vintage comics, pulp

magazine, and movie scripts and memorabilia. He must have purchased

the Grill/Binkin collection of Lovecraft manuscripts in the late

1970s or early 1980s.

This is a follow-up, bringing the story to the present as far as I am able.

The original blog post received

the following comment from someone who signed their name only as

JohnK:

“Quite a few pieces of the Grill Collection wound up in the 'Undead' Book Sail (John McLaughlin) catalog 1984. McLaughlin also had the Cats Of Ulthar manuscript for sale in the early 90's as I recall. McLaughlin was eccentric to say the least, he had a shop in Orange Ca. that was hardly ever open to the public and was loaded with weird collector's items that he really wasn't interested in selling.“After McLaughlin passed away many of his treasures were auctioned off by Heritage, including the mostly unsold Lovecraft Grill collection. McLaughlin's dream like many collectors was to have a museum devoted to his collections. His family had other ideas. I actually looked at that Dracula script at his shop one time, it was stashed in a pile of other equally rare stuff.”

I

remember that catalog primarily for its long six-page description of

the typescript of Dracula

(originally titled "The Undead"), and the fact that the

package in which it was sent was marked: "Open with Care,

Contents UNDEAD." I'd completely forgotten that the catalog

included HPL and Weird

Tales

materials. The catalog itself is dated 1984, but my copy wasn't

mailed until February 28th, 1985.

And

sure enough, among all of the Lovecraftiana are listings for the

manuscripts of “The Cats of Ulthar” and “Some Dutch Footprints

in New England,” as well as Lovecraft's Astronomical Notebook,

1909-1915, among many other items. The Lovecraft material is quite

extensive, and runs some forty-six heavily descriptive pages,

covering items 355 through 468. Additionally, there are many

photographs of the various items.

|

| Cover to the 1984 Undead Book Sail catalog |

The

catalog itself is a lavish production. Most copies were done in trade

paperback, with a new color cover by Rowena Morrill, and new

materials by Ray Bradbury, Robert Bloch, and others. The print run

was evidently fairly large, as the colophon notes that the edition

consisted of 1,400 numbered copies, of which one thousand were bound

in wrappers, and four hundred bound as deluxe hardcovers (with extra

material, and the signatures of the contributors). On top of the

1,400 copies, another one hundred fifty were made for the publisher's

use, including fifty copies bound in half-leather for presentation to

contributors. The copies were hand-numbered with an ink compound that

contained actual human blood. (To add to the absurdity, the inserted

errata slip, correcting only one item's price, has a notation that

“This errata is limited to 1500 copies.” Presumably the

contributor copies were given out without this photocopied errata

slip.)

The

catalog is subtitled the “16th Anniversary Catalogue” of the Book

Sail out of Orange, California. It was edited and catalogued by

Bruce Francis, and published and coordinated by John McLaughlin. It

is probably fair to call the whole enterprise eccentric, for,

basically, it's a kind of vanity publication to show off the

materials that McLaughlin had collected and which he really didn't

want to sell. (The high prices alone are evidence of a desire not to

sell the materials.) And the catalogue itself was sold to inquiring

customers. I don't remember the price, but it wasn't cheap, and one

was really paying for the privilege to read the often lengthy

descriptions of rare and unique items, of which the Stoker manuscript

was the prized example.

The

proprietor of the Book Sail must also be described as eccentric. John

Kevin McLaughlin (1942-2005) was the only child of an IBM executive

and his wife. He grew up in Endicott, New York, and graduated from

high school there, after which he attended college at World Campus,

which was a float that went around the world. He married (and

divorced) twice, and was survived by two sons from his first

marriage. He founded the Book Sail in Anaheim in 1968, and moved it

to a larger location in Orange in 1975. Meanwhile he amassed a

legendary collection of antiquarian books, vintage comics, pulp

magazine, and movie scripts and memorabilia. He must have purchased

the Grill/Binkin collection of Lovecraft manuscripts in the late

1970s or early 1980s.

The

proprietor of the Book Sail must also be described as eccentric. John

Kevin McLaughlin (1942-2005) was the only child of an IBM executive

and his wife. He grew up in Endicott, New York, and graduated from

high school there, after which he attended college at World Campus,

which was a float that went around the world. He married (and

divorced) twice, and was survived by two sons from his first

marriage. He founded the Book Sail in Anaheim in 1968, and moved it

to a larger location in Orange in 1975. Meanwhile he amassed a

legendary collection of antiquarian books, vintage comics, pulp

magazine, and movie scripts and memorabilia. He must have purchased

the Grill/Binkin collection of Lovecraft manuscripts in the late

1970s or early 1980s.

McLaughlin

was reportedly given lavish amounts of money by his father, and

thereby was able to build his collections. His parents died in

Endicott in the early 1990s, and McLaughlin died there at the age of

63 in June 2005. In August 2006, major chunks of his collections,

including it seems much of the Lovecraftiana, was auctioned by

Heritage Auction Galleries and Diamond International Galleries. Some

of McLaughlin's collection—this looks mostly to be movie ephemera

(posters, scripts, photos, contracts, etc.)— ended up in "The

John McLaughlin Collection of Popular Culture" in Special

Collections at Binghamton University.

Thus,

through the auction of McLaughlin's collections, much of what had

been the Grill/Binkin collection of Lovecraftiana re-entered the

market, and was apparently completely dispersed. Many of these

materials are probably still out there somewhere, though individual

items are not easily located, and it appears that most of it did not

end up in institutions or libraries.

At

least the collection per

se

did not end up in a dumpster.

Saturday, July 6, 2019

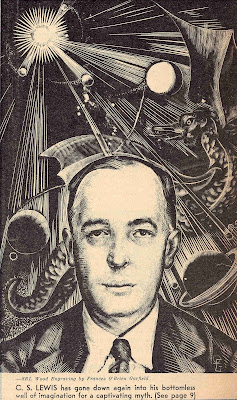

C.S. Lewis on the Covers of 1940s American Magazines

It is well-known that C.S. Lewis appeared on the front cover of Time magazine in the 1940s. The specific issue date was that of 8 September 1947, and the artist was Boris Artzybasheff. See it at right.

It is well-known that C.S. Lewis appeared on the front cover of Time magazine in the 1940s. The specific issue date was that of 8 September 1947, and the artist was Boris Artzybasheff. See it at right. Less-known is the fact that Lewis had appeared some three years earlier on the cover of The Saturday Review of Literature, accompanying a review (by Leonard Bacon) of the U.S. edition of Perelandra. The specific issue date was 8 April 1944, and the wood engraving for the cover was by Frances O'Brien Garfield. The artist was apparently given only a headshot of a rather weary-looking C.S. Lewis to use in making the cover. This headshot was apparently a publicity photo used by the U.S. publisher Macmillan, as it also appeared next to contemporary American reviews of some of Lewis's books.

Here's a close-up of the illustration itself, with the scan of Lewis's headshot below it for comparison.

Monday, July 1, 2019

A Christopher Morley Quote Produced a Conundrum

It began with a quotation attributed to Christopher Morley (1890-1957). A nice quote, for which the source is usually not given. Yet an interesting piece of bibliographical ephemera seems to helps. Here's a photo of it (click on the image to see it larger), with the quotation:

It is undated, but it states that it is an excerpt from Morley's final novel The Man Who Made Friends with Himself, which was published in April 1949. Yet this citation is wrong, and the quote is even punctuated incorrectly, with one word wrong. (See the real source, properly punctuated, at the bottom of this post.) The printer is identified as Herbert W. Simpson of Evansville, Indiana. He was born in 1904, and died in 1970. He and his wife Dora (1909-1995) are buried together in Evansville. His firm, Herbert W. Simpson Inc. was incorporated in Evansville in October 1943 as a business of general printing, engraving, lithography, and electrotyping. Simpson seems to have done a number of such pieces of ephemera, only a few of which are dated. These include Politics and the English Language: An Essay Printed as a Christmas Keepsake for the Typophiles (1947) by George Orwell, and The Feather-Vendor Zodiac Calendar, 1951 (1951) by W.A. Dwiggins. Simpson seems to have been most active in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

It turns out that Simpson published two additional pieces of Christopher Morley ephemera (and if anyone has copies, I have a friend who wants them for his Morley collection. Really.). Both, of course, are undated, but here are the details from some library catalogues:

A Birthday Greeting for William Shakespeare, 23 April 1564-23 April 1616 by Christopher Morley. Evansville, IN: Herbert W. Simpson, [no date].

Includes quotation from Morley's Shakespeare and Hawaii (1933).

1 folded sheet ([3] pages).

"In the solemn vein of occasional advertising pronouncements: this piece is the second of a series. While ostensibly a birthday greeting, it is also a printers' potage cooked up from contributions by several hands. Credit is directly given to the three writers involved with the flavor of words. The illustrations are by Merrill Snethen and the types are various sizes of Caslon 471."

Contains Shakespeare's "Sonnet number sixty" and "A letter from Christopher Morley", regarding the Sonnets.

Note: Merrill Snethen (1904-1974) was a native of Evansville, educated at the Art Institute of Chicago.

Energy Is Not Endless . . . by Christopher Morley.

Evansville, IN: Herbert W. Simpson, [no date].

"Energy is not endless, better hoard it for your own work. Be intangible and hard to catch; be secret and proud and inwardly unconformable. Say yes and don’t mean it; pretend to agree; dodge every kind of organization, and evade, elude, recede. Be about your own affairs, as you would also forbear from others at theirs, and thereby show your respect for the holiest ghost we know, the creative imagination."

Broadside

From a tribute to Don Marquis (1878-1937) by Morley, "O Rare Don Marquis", The Saturday Review of Literature, 8 January 1938, and collected in Morley's Letters of Askance (1939).

The correct source of Morley's quotation is his column entitled "Brief Case; or, Every Man His Own Bartlett," which appeared in the 6 November 1948 issue of The Saturday Review of Literature, page 20. The epigrams in the column are rather gloomy for Morley, but the final one is more uplifting (and also punctuated more euphoniously):

*[sic] it reads "always part of" not "always a part of" as in the card shown above.

It is undated, but it states that it is an excerpt from Morley's final novel The Man Who Made Friends with Himself, which was published in April 1949. Yet this citation is wrong, and the quote is even punctuated incorrectly, with one word wrong. (See the real source, properly punctuated, at the bottom of this post.) The printer is identified as Herbert W. Simpson of Evansville, Indiana. He was born in 1904, and died in 1970. He and his wife Dora (1909-1995) are buried together in Evansville. His firm, Herbert W. Simpson Inc. was incorporated in Evansville in October 1943 as a business of general printing, engraving, lithography, and electrotyping. Simpson seems to have done a number of such pieces of ephemera, only a few of which are dated. These include Politics and the English Language: An Essay Printed as a Christmas Keepsake for the Typophiles (1947) by George Orwell, and The Feather-Vendor Zodiac Calendar, 1951 (1951) by W.A. Dwiggins. Simpson seems to have been most active in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

It turns out that Simpson published two additional pieces of Christopher Morley ephemera (and if anyone has copies, I have a friend who wants them for his Morley collection. Really.). Both, of course, are undated, but here are the details from some library catalogues:

A Birthday Greeting for William Shakespeare, 23 April 1564-23 April 1616 by Christopher Morley. Evansville, IN: Herbert W. Simpson, [no date].

Includes quotation from Morley's Shakespeare and Hawaii (1933).

1 folded sheet ([3] pages).

"In the solemn vein of occasional advertising pronouncements: this piece is the second of a series. While ostensibly a birthday greeting, it is also a printers' potage cooked up from contributions by several hands. Credit is directly given to the three writers involved with the flavor of words. The illustrations are by Merrill Snethen and the types are various sizes of Caslon 471."

Contains Shakespeare's "Sonnet number sixty" and "A letter from Christopher Morley", regarding the Sonnets.

Note: Merrill Snethen (1904-1974) was a native of Evansville, educated at the Art Institute of Chicago.

Energy Is Not Endless . . . by Christopher Morley.

Evansville, IN: Herbert W. Simpson, [no date].

"Energy is not endless, better hoard it for your own work. Be intangible and hard to catch; be secret and proud and inwardly unconformable. Say yes and don’t mean it; pretend to agree; dodge every kind of organization, and evade, elude, recede. Be about your own affairs, as you would also forbear from others at theirs, and thereby show your respect for the holiest ghost we know, the creative imagination."

Broadside

From a tribute to Don Marquis (1878-1937) by Morley, "O Rare Don Marquis", The Saturday Review of Literature, 8 January 1938, and collected in Morley's Letters of Askance (1939).

The correct source of Morley's quotation is his column entitled "Brief Case; or, Every Man His Own Bartlett," which appeared in the 6 November 1948 issue of The Saturday Review of Literature, page 20. The epigrams in the column are rather gloomy for Morley, but the final one is more uplifting (and also punctuated more euphoniously):

Read, every day, something no one else is reading. Think, every day, something no one else is thinking. Do, every day, something no one else would be silly enough to do.

It is bad for the mind to be always part of a unanimity.*

*[sic] it reads "always part of" not "always a part of" as in the card shown above.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)